Hamsun exhibition

NARRATOR IN INTRODUCTION FILM

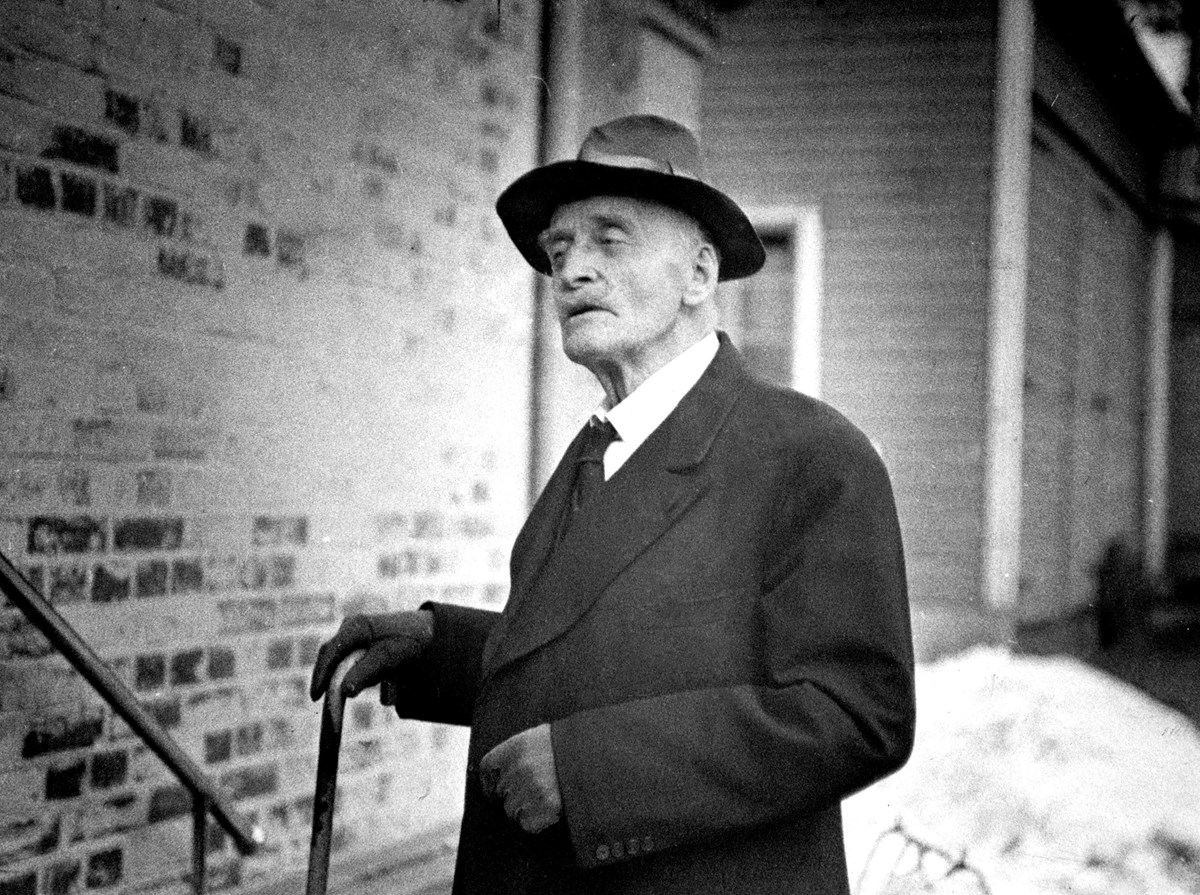

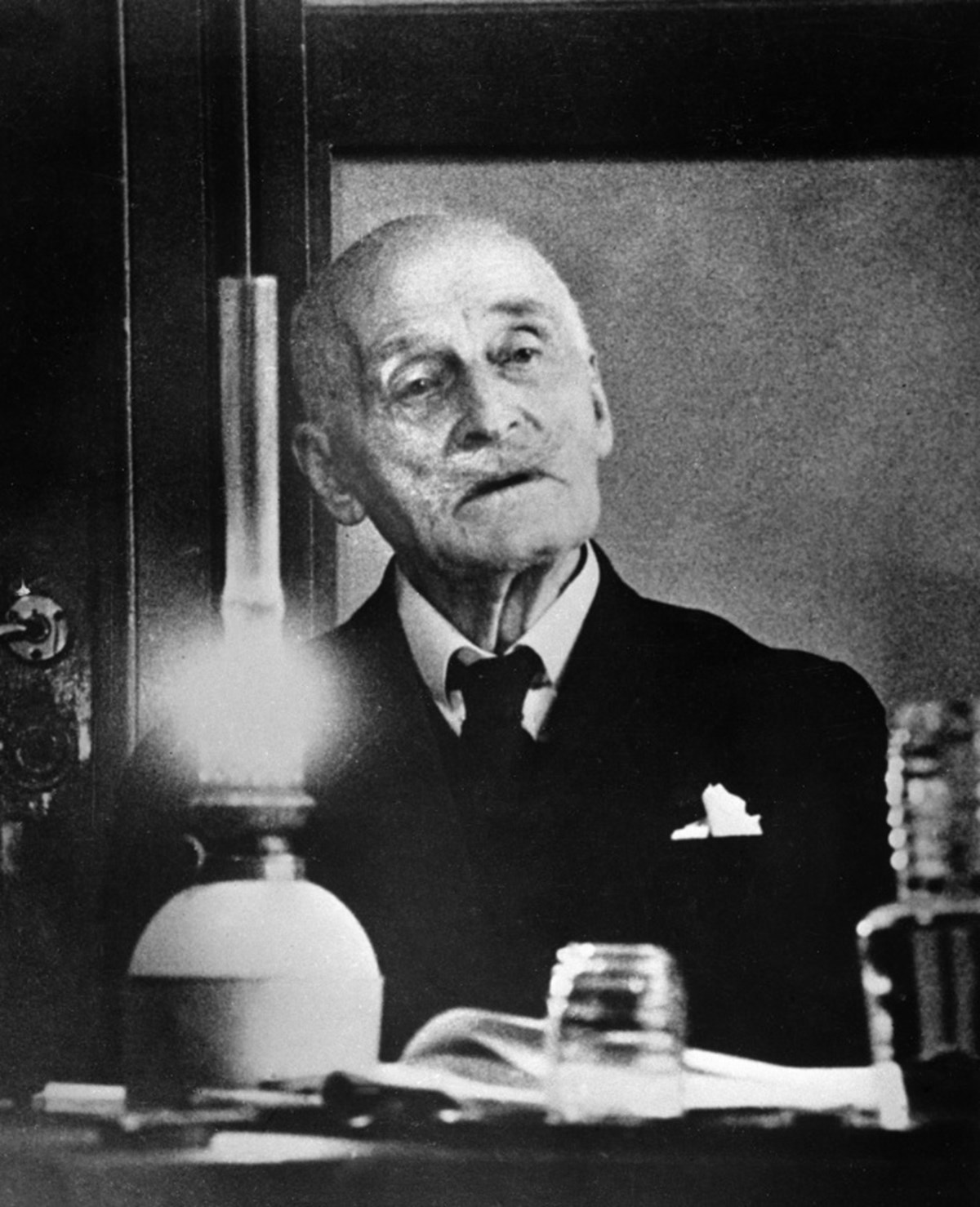

Knut Hamsun is one of Norway's most renowned and read authors. He was born Knud Pedersen on 4 August 1859 in Lom in Gudbrandsdalen.

His made his début at age 18, but the breakthrough came in 1890 with the modernist novel Hunger. The novel was first serialized in a periodical and later published as a book. Hunger and Hamsun's writing style was an important work that inspired his contemporaries, and has continued to inspire later generations of authors.

Hamsun's most read, and perhaps most renowned, novel is Victoria. Decidedly the most popular of his novels, Victoria is about the love between Johannes, a miller’s son, and Victoria, the daughter of a wealthy landowner. It is a story of impossible and tragic love that has captivated generation after generation of young people.

For Hamsun personally it was Growth of the Soil, a work completed in 1917, that brought him the most recognition. The novel follows the story of Isak and Inger who builds the farm Sellanraa in the wilderness. Hamsun was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature three times, but it was only when he was assessed based on only one body of work that he was awarded the prize in 1920. This work was Growth of the Soil.

When Knut Hamsun was five years old, the family moved to Hamarøy in Nordland where spent the rest of his childhood. This Northern-Norwegian scenery and rural community he became part of form the backdrop for several of his stories. The most renowned are perhaps the novels about the vagabond August in the Wayfarers trilogy.

Knut Hamsun lived at Hamarøy until he was 18 years old. He then led a drifter’s life for many years, which took him to Bergen and Gjøvik, Copenhagen and Christiania, USA and Paris. He took on casual and temporary work to support himself, and at the same time focussed on his writing.

In 1908, Knut Hamsun met the actress Anne Marie Andersen. She was due to perform in Hamsun's play At the Gate of the Kingdom at the National Theatre in Oslo. The two met to discuss her role, and this was the start of a lifelong love story between Knut and the 22 years younger Marie. They married the very next year.

Knut and Marie Hamsun had four children. The three eldest, Tore, Arild and Ellinor, were born at Hamarøy where the couple bought their first farm, Skogheim, in 1911. The youngest daughter, Cecilia, was born in Larvik where the family lived for a short period of time. This was also the year Hamsun completed Growth of the Soil.

In 1918, Hamsun purchased Nørholm – a country estate on the outskirts of Grimstad, in Eide municipality – and the family moved in in November. Hamsun took a loan in Grimstad Sparebank in order to buy the estate. The bank had its offices on the ground floor of this building.

During the Second World War, Hamsun supported the German occupation of Norway and wrote several articles supporting this view. In 1943, he met Adolf Hitler on a journey to Germany. After the war, he was charged with treason and for conspiracy to violate Norway's autonomy and constitution. The charges were dropped following a forensic psychiatric report that concluded that Hamsun had “permanently impaired mental faculties”.

In 1946, however, the Directorate for Compensations served him a summons for his membership of the National Unity party. The following year, he was sentenced to pay the Norwegian state NOK 425 000 in compensation. The trial was held on the first floor of this building.

Hamsun last novel, with the symbolic title The Ring is Closed, was published in 1936. Perhaps it was meant to be his final publication. This was not to be. When in police custody and during the court proceedings, he reflected on and wrote down his experiences. This work was given the title On Overgrown Paths. He ends the book with the following words: “Today the Supreme Court has handed down its verdict, and I end my writing.” He could then look back on a life as an author spanning 72 years.

Knut Hamsun died at his home, Nørholm, on 19 February 1952.

EXHIBITION TEXTS GROUND FLOOR

1. Purchase of Nørholm

During the First World War, Knut Hamsun had his heart set on buying a country estate. He engaged a number of people in the search. One of these was shipowner and mayor of Vestre Moland, Tønnes A. Birknes. He was a friend of Hamsun from his time in Lillesand.

Birknes found Nørholm manor and negotiated with its owner, Leif Longum. Longum sold the property to Hamsun in 1918. Knut Hamsun moved to the farm with his wife, Marie Hamsun, and their four children in November that same year. The purchase price was around NOK 200 000. Hamsun financed this through a loan from Grimstad Sparebank. The bank had its premises here in Storgaten 44.

Letter to Birknes, 17 May 1918:

(The manor) shall first and foremost be located by the sea, have electricity and water supply and some farmland (80-150 daa infields), but plenty of forest and a harbour, close to a school, but does not have to be close to a town. An old and dilapidated and neglected “nobleman’s manor” would suffice, I would get it back on its feet and farm the land. (…) I do not wish to have a tenant farmer, their work is too slipshod, I want to run the farm myself, this is what interests me.

Letter to Birknes, 20 July 2018:

But how are we progressing with Narholmen, have you managed to see the good Longum sober? Perhaps it is not his desire to sell at all? I wait in great suspense for your response, because this was the only place that almost fully attracted me in every way. The house was not big enough and nor was it pretty, but the setting was so remarkably beautiful, and the entire farm was beautiful. Let me know if you believe that it is futile for me to think of Longum’s place.

2. Modernisation

Hamsun was a resourceful and impatient estate owner who had multiple projects on the go simultaneously. His first undertaking was to erect the estate manager’s building.

The outbuilding, serving as both cowshed and hay barn, was renovated and extended. Hamsun also wanted to extend the manure cellar, but there was a rock in the way. Dynamite was placed underneath the obstacle, and as a result Hamsun blasted away parts of the new outbuilding.

The manor house was converted and extended in every direction in 1922. Hamsun designed the building himself, and he also supervised the work. Water and electricity had been installed the previous year. The garden was landscaped as per Hamsun's instructions. He wanted a flat and symmetrical garden surrounded by hand-forged fencing.

He was a prudent man, and often used the expression “å vøle om”. This meant to repair to unusable, turn ugly items into attractive ones, and strengthen the weak into something sturdy.

3. Farming

Wetland on the property was turned into arable land, and was used to grow rye. Forest tracks leading to the marshes made access to the fields easier. The fields closest to the farm were used as cultivated pastures.

Hamsun expanded his indoor herd from eight to 40 cows. He looked after the animals himself, and noted down how much milk each cow produced.

Forestry was an area with which Hamsun was unfamiliar. He planted a lot of trees, but did not wish to log the forest. In his opinion, there were too few trees at Nørholm.

Hamsun read specialist literature, also on farming. He acquired a tractor and other modern machinery early on. He was also among the first to build a silo.

4. Writer’s cottage

Hamsun turned one of the cotter's farms at Nørholm into a writer’s cottage. He had the building moved from its original location to within easy reach of the manor house, and painted it white. He referred to the cottage as “my house”. This was where he wrote his final six novels. It was also home to Hamsun’s library, comprising over 6200 books.

4. Family car

Knut Hamsun bought his first car in 1922, but it was Marie who mastered the art of driving. The car brought pleasure to the whole family, and was used to drive the children into town and for excursion. One of the couple’s traditions was to go on road trip around Hamsun's birthday on 4 August. Every year at this time, journalists visited Nørholm to interview Hamsun – something he detested. Hamsun considered the car a fantastic buy, and referred to it as a “home on wheels”.

5. Family life

Hamsun in a letter to his friend, Karlfeldt, on 7 January 1922:

It is the children our entire lives are about – in spring I will buy them a car to go to the towns, and they already have a puppy and a doll’s house and boxing gloves and gramophone and all sorts of animals in the barn.

Knut and Marie Hamsun had four children together. The three eldest were born at Hamarøy, and the youngest in Larvik. The eldest was Tore, then there was Arild, and finally Ellinor and Cecilia. For the first few years, the children attended Vaagsholt school in Eide. Hamsun was sceptical to school, which in his opinion was slavery. When Tore returned home from his first day at school and told him that they made pancakes for everyone, he was reassured.

ARTEFACT TEXTS GROUND FLOOR:

11. Hamsun bought this Edison gramophone in Arendal in autumn 1920. It was a great success at children’s and Christmas parties.

Tore Hamsun writes in his memoirs:

Christmas 1920 brought the children an astounding experience. My father played music on a gramophone! To their astonishment, they heard song and music coming from a cabinet. It was a large, newly acquired Edison gramophone, camouflaged as a furniture, that emitted these sounds, so very different from the organ in Eide church and Markussen’s single-string instrument. A first meeting with canned music.

12. Knut Hamsun was commissioned to write texts for the 1932 calendar published by Dyrebeskyttelsen – the national animal protection society. He chose to write about Nørholm and the children’s relationship with animals.

January was dedicated to the eldest daughter, Ellinor.

February talked about his daughter Cecilia and her hen.

In June, Arild and horses were the main characters.

July was about the eldest son, Tore.

The December page was signed by Knut Hamsun.

Dyrebeskyttelsen’s calendar 1932. Archive ref: PA-1435, Personalia F L0194, Hamsun, KUBEN.

13. Marie Hamsun (1881-1969) made her début as a children’s author with Bygdebarn. Hjemme og paa sæteren. (A Norwegian Family) in 1924. It was an instant success, and was translated into several languages.

14. The nursery had a refectory table where the children drew, played and worked. Knut Hamsun loved card games, and often sat at this table in the evenings playing “fives” with Tore and Arild.

15. Knut Hamsun corresponded with his youngest daughter, Cecilia, when he went away to write. This is a letter sent from Egersund in 1932. Cecilia was then 17 years old.

Dear Cecilia!

Thank you for such an immaculate letter from you, written in the most beautiful hand on the very best of paper and with a gold foiled envelope! At first I did not realise who it was from, because I did not recognise the writing, that is how neatly you have written. Well, you write better than me all of you. – Such sad news about Dux, his death pains me, for he was a truly kind and intelligent dog. I suppose we must try to find a new dog, but it will not be one like Dux. – No, dear Cecilia, it is not possible to go to the cinema for free. I enclose a note for you and one for Ellinor so that you may enjoy yourselves before the holiday comes to an end. I hear that Ellinor would like to return to Germany to learn French, but you have to tell her to reconsider. Tell her to go to straight to Belgium, then she will learn to speak French much, much faster – she will see that she can then fend for herself in French in only a few weeks. – I strive to do some work, but I am no longer so young and adept. It is with me as with Dux, we are old. But is a sin to complain, we shall be in good spirits – Bless you all, you little ones.

Papa

Letter from Knut Hamsun to his daughter Cecilia. Archive ref: PA-1435, Personalia F L0180, Hamsun, KUBEN.

16. Hamsun’s herd of cows counted 40 at the most. In March 1921, the farm delivered 1419 kg milk to Grimstad Meieribolag.

Statement of accounts from Grimstad Meieribolag for March 1921. Archive ref: PA-1435, Personalia F L0180, Hamsun, KUBEN.

17. Tore, Ellinor and Cecilia were pupils at Vaagsholt school. Tore was enrolled in September 1919, Ellinor in September 1922, and Cecilia in October 1923. A school report for Vaagsholt elementary school in Eide municipality shows an overview of the grades achieved by the girl in the various subjects.

School report for Vaagsholt. Archive ref: KA0925-PK, Eide kommune 06, Skole L0028, Vågsholt.

EXHIBITION TEXTS 1. FLOOR

6. Arrest

Knut and Marie Hamsun were initially placed under house arrest at Nørholm due to their involvements during the Second World War. The couple had supported the occupation forces.

On 14 June 1945, Hamsun was arrested and placed in custody at old Grimstad hospital. He remained there until 2 September, and was then transferred to Landvik nursery home.

6. Charged with treason

In June 1945, Knut Hamsun was charged with two criminal acts. These were breach of §86 of the General Civil Penal Code relating to treason, and also §140 relating to conspiracy to violate Norway's autonomy and constitution.

A few weeks later, he was charged with consenting to membership of the National Unity party. This was a criminal offence as of 8 April 1940.

The prosecution was based on Hamsun's articles, his statements during the war, and his application for membership of the National Unity party.

7. Psychiatric assessment and decision not to proceed with the case

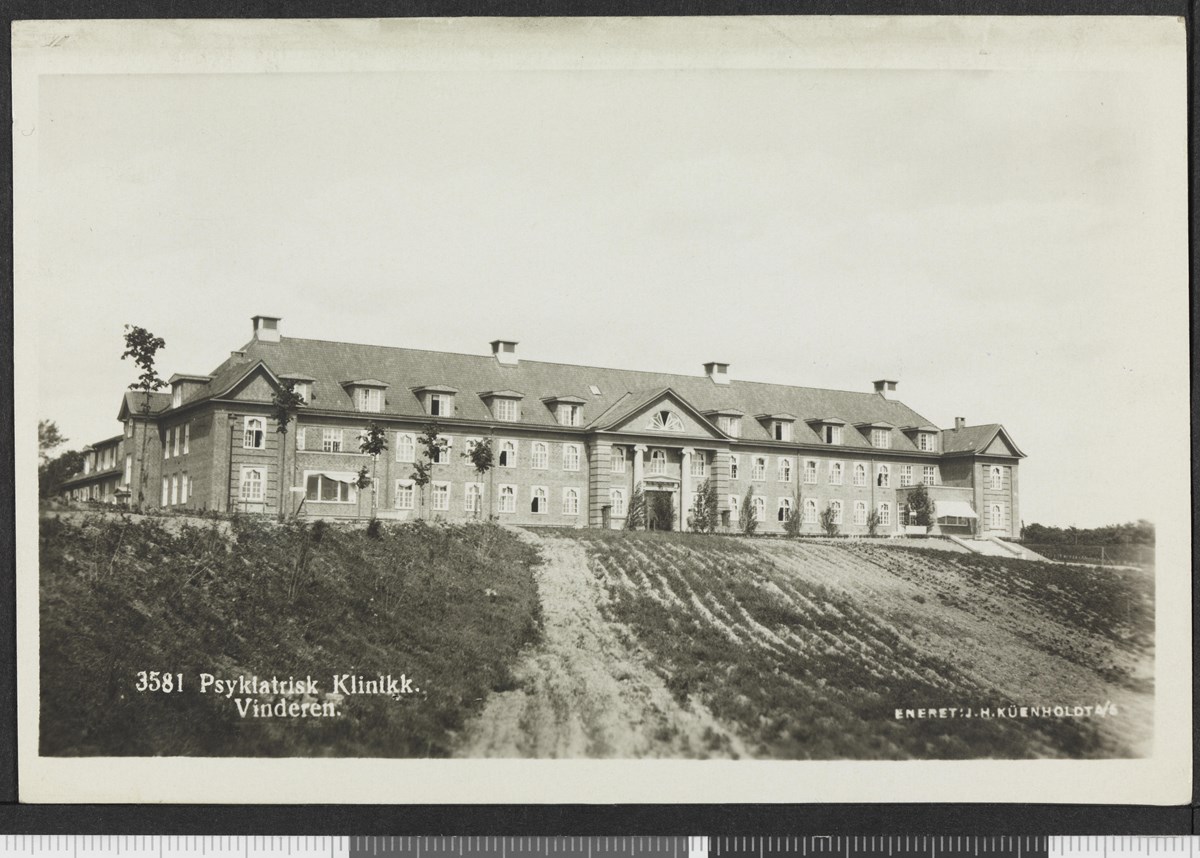

Hamsun was referred for forensic psychiatric examination in October 1945. Professor Dr. med. Gabriel Langfeldt and senior consultant Dr. med. Ørnulv Ødegård were appointed as expert advisors. The judicial observation was conducted at Vinderen psychiatric clinic in Oslo.

The statement was submitted in February 1946. Their conclusion was:

We do not regard Knut Hamsun as insane and assume that he has not been insane during the period of the acts in question. We regard him as a person with permanently impaired mental faculties, and assume that there is little if no chance of his crimes being repeated.

Having considered this statement, the prosecution authority decided not to initiate criminal proceedings.

8. Legal proceedings and claim for damages

Instead, an action for damages was brought against Hamsun based on his membership of National Unity.

Hamsun was charged and convicted under §2 and §22 of the Treason and Collaboration Act of 21 February 1947. This act was a continuation of the treason and collaboration arrangements adopted during and immediately after the war.

§2 stated that it was a criminal offence to be part of, or to apply or consent to be part of, the National Unity party. §22 stated that those having committed an act as defined in §2, had to answer for the damage inflicted on society by National Unity during their period of membership. This is why Hamsun's membership of National Unity was a key argument in the court case.

9. Trial and judgement

The main hearing took place on 16 December 1947 in Sand district court located here in Storgaten 44. Proceedings lasted for one day only. No witnesses were called in the case. Hamsun held a defence speech where he denied having been a member of National Unity. Judgement was pronounced three days later. Hamsun was sentenced to pay NOK 425 000 in compensation. There was dissent among the justices; they were not in agreement. Judge Eide was of the opinion that Hamsun's membership of National Unity had not been proven, whereas lay assessors Flaa and Egeland were of the opinion that it had. The evidence was National Unity’s archive with Hamsun’s membership number 26 000.

9. Supreme Court appeal

The judgement passed by Sand district court was appealed to the Supreme Court by both parties. The case was heard by the Supreme Court in June 1948, and judgement was passed on 23 June.

The Supreme Court concluded unanimously that Hamsun had been a member of National Unity during the war. The claim for damages was reduced to NOK 325 000. Hamsun was also sentenced to pay the legal costs for both trials. Hamsun settled his outstandings, and paid the amount in full. He also managed to retain ownership of Nørholm.

10. Defence speech

What might knock me down is solely my articles in the newspapers. There is nothing else that can be brought against me. As far as that goes, my accounts are very simple and straightforward. I never denounced anyone, never took part in meetings, wasn't even involved in black-marketing. I never gave anything to the storm troopers, or to any other branch for the National Union party, of which I’m now said to have been a member. Nothing, in short.

I was never a member of National Union. I tried to understand what National Union was about, I tried to get to the bottom of it, but it didn’t come to anything. However, it may very well be that I wrote in the spirit of National Union now and then. I don’t know, because I don’t know what the spirit of National Union is. But it may well have happened that I wrote in the spirit of National Union, that something had seeped into me from the newspapers that I read. In any case my articles are there for anyone to see. I’m not trying to minimise them, to make them more trifling than they are, it may be bad enough as it is. On the contrary, I am ready to answer for them now as before, as I have always been. (…)

And no one told me that what I was writing was wrong, no one in the entire country. I sat in my room alone, thrown exclusively upon my own resources. I didn’t hear, I was so deaf that nobody could have anything to do with me. (…) For months, for years, during all those years, that’s how it was. And never a hint from anyone. I was no runaway. My name was fairly well known in this country. I believed I had friends in both Norwegian camps, both among the quislings and the so-called patriots. But never the smallest hint, a bit of good advice from the outside world. No, the world was very careful to refrain from that. (…) Under these circumstances I had nothing to go by except my two newspapers, Aftenposten and Fritt Folk, and those two papers never said there was anything wrong with what I wrote. On the contrary.

And what I wrote was not wrong. It was not wrong when I wrote it. It was right, and what I wrote was right. (…)

So when I sat there and wrote as best I could and sent telegrams night and day, I was betraying my country, they say. I was a traitor, they say. Let that go. But I didn’t see it that way – I didn’t feel that way, nor do I feel that way today. I am at peace with myself, my conscience is quite clear.

I have a fairy high regard for public opinion. I have an even higher regard for our Norwegian judicial system, but I do not regard it as highly as I do my own consciousness for what is good and bad, what is right and wrong. I am old enough to have a rule of conduct for myself, and this is mine.

ARTEFACT TEXTS 1. FLOOR:

18. The accusation of treason was based on Hamsun's many newspaper articles during the war. His final article was published the day before the war ended. It was an obituary for Adolf Hitler in the newspaper Aftenposten on 7 May 1945.

19. Langfeldt and Ødegård chose to publish the forensic psychiatric statement in its entirety in 1978 because segments had already been made public elsewhere.

20. The novel On Overgrown Paths was published by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag in 1949. Knut Hamsun started writing the book when he was arrested. In this work, he describes how he experienced the arrest and the process leading to the final judgement.

21. Facsimile of membership record no. 26000

One of the most important pieces of evidence presented by the police and prosecution authority was the questionnaire completed by Hamsun. This was attached as an appendix to his application for membership of National Unity.

Silk ribbons across the chairs:

Defendant Knut Hamsun

Defence counsel Sigrid Stray

Lay assessor Ommund Egeland

Lay assessor Jakob Flaa

Judge Sverre Eide

Prosecutor Odd Vinje

Court clerk Ågot Ribe

Tickets

Tickets